Cortisol and Decision-Making: Tunnel Vision, Habit Circuit Takeover, Prosocial Behavior, and Manipulation Vulnerability

Leaders in high-stress environments often pride themselves on their decision-making prowess under pressure. Whether it’s making a snap judgment during an emergency or negotiating under a deadline, many assume that stress simply “comes with the territory” and that good leaders can compartmentalize it. However, the reality is far more complex. Cortisol, the primary stress hormone, can sharpen some mental functions while impairing others, and its effects depend on timing, context, and even the decision-maker's gender or personality.

Cortisol’s Cognitive Effects: Selective Memory and Attention

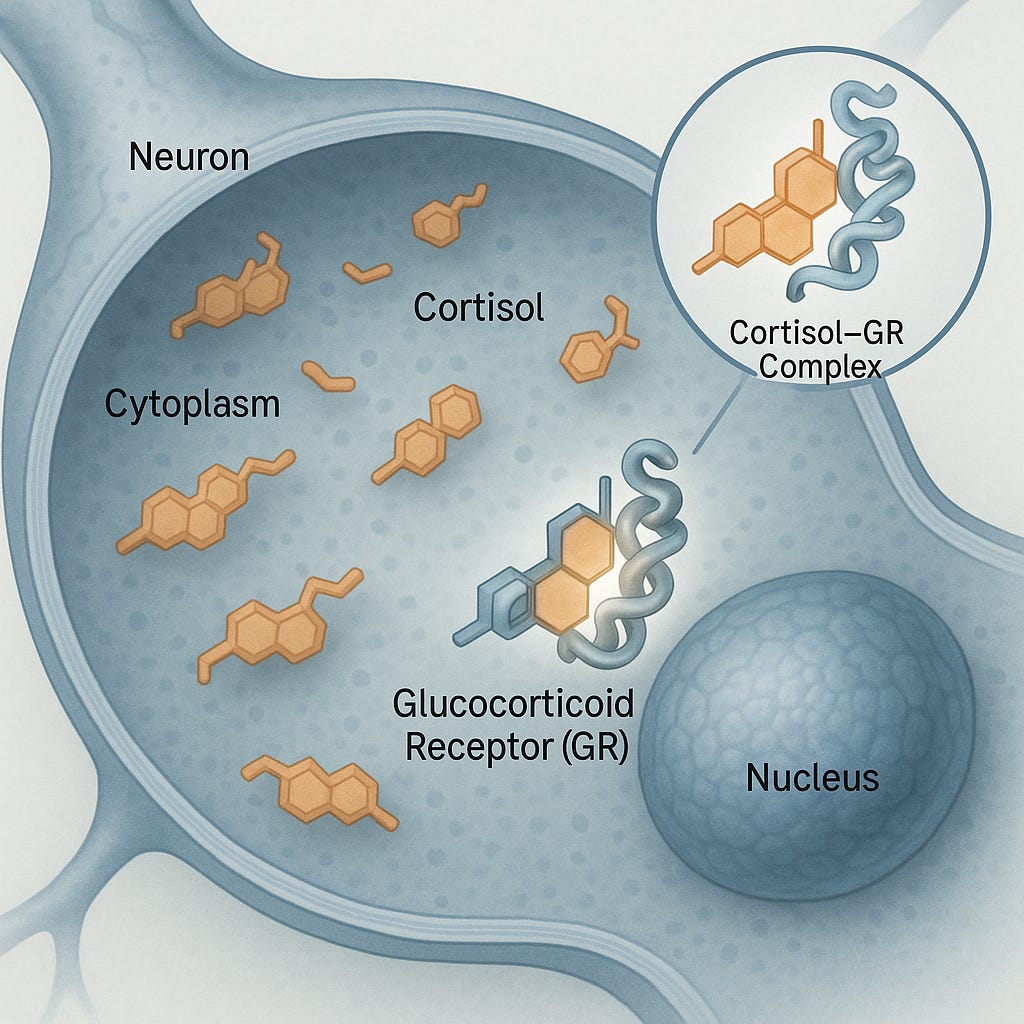

To understand how cortisol influences our thinking, we must first grasp how this stress hormone operates in the brain. As discussed in the previous article, cortisol is released through the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis when we encounter stressors. Once in the bloodstream, cortisol exerts its effects by binding to specialized cortisol receptors (i.e., protein structures that act like molecular locks) with cortisol as the key. The cortisol receptors are abundant throughout the brain, but they are particularly concentrated in regions critical for memory and executive function: the hippocampus (which processes and consolidates memories) and the prefrontal cortex (the brain's command center for reasoning, planning, and impulse control). When cortisol binds to these receptors, it triggers changes in gene expression and neural activity that can directly influence our ability to think and remember.

Memory Formation Under Stress: The Tunnel Vision Effect

One well-documented effect of cortisol is on memory formation: high acute cortisol levels tend to enhance memory for the core aspects of an emotional event (you will vividly recall the main threat or outcome) but impair recall of peripheral details. This is why you might remember the decisive point of a heated debate in a meeting, especially if you felt threatened when a more senior team member threatened you not to move forward with a proposed project. But you later struggle to recall who else was present or what minor points were raised.

This memory selectivity is actually adaptive. In a crisis, you are under acute stress. Cortisol interacts with the amygdala (a brain region associated with emotion processing) and the hippocampus (a brain region associated with memory consolidation). This interaction helps your brain prioritize the most relevant information for survival and decision-making. However, if you are unaware of this mechanism, the intensified focusing effect can lead to tunnel vision. You may weigh the most salient piece of information, which is often the "loudest" or most emotional issue, more heavily than other considerations that are important for a balanced decision.

Executive Function and the Prefrontal Cortex Under Stress

Cortisol also influences the prefrontal cortex (PFC), the brain's executive headquarters responsible for working memory (holding information in mind while using it), attention control (focusing on relevant details), and inhibition of impulses (stopping yourself from acting rashly). The PFC houses high concentrations of cortisol receptors, making it particularly sensitive to stress hormone fluctuations. Under moderate stress, cortisol working alongside norepinephrine (another stress chemical) can transiently enhance certain types of attention and habit-based learning. In fact, elevated cortisol biases the brain toward what we call "habit memory" or intuitive responses, rather than deliberate analytical thinking. This neurochemical shift means that when cortisol is elevated, we might rely more heavily on gut feelings or well-practiced routines stored in deeper brain circuits.

For an experienced emergency responder, this cortisol-driven shift can be advantageous. You fall back on training without overthinking, which allows rapid deployment of proven protocols. However, if the situation is novel or requires creative problem-solving, that same neurological bias can be detrimental. High cortisol impairs the PFC's more flexible, "think outside the box" operations while more primitive habit circuits and emotional circuits assume control. This neurobiological reality has direct implications for workplace innovation. Chronic stress and elevated cortisol can suppress divergent thinking and creative problem-solving. If you want your team to be innovative, you should work to lower team members' cortisol levels by removing chronic stressors, such as unclear role expectations (role ambiguity), micromanagement, excessive workload, or constant interruptions that prevent deep focus. Consider a product development team facing tight deadlines: while some acute stress might sharpen focus on immediate tasks, chronic elevation of cortisol will bias team members toward familiar solutions rather than breakthrough innovations. The stressed brain defaults to "what we've always done" rather than exploring uncharted territory. It explains why many organizations find that their most creative insights emerge during lower-pressure periods or after implementing stress-reduction initiatives that allow the prefrontal cortex to fully engage its flexible, analytical capabilities.

Risk-Taking Under Stress: Heightened or Diminished?

Perhaps the most scrutinized aspect of decision-making under cortisol's influence is risk-taking behavior. Do stressed leaders become more daring or more cautious? Research findings have been somewhat inconsistent, but a pattern emerges when we consider timing and context. Immediately after a stressful event, as cortisol is peaking, decision-making can shift to favor immediate rewards over larger delayed gains. However, the picture isn't simply "stress makes you reckless." The content and temporal nature of the decision matter substantially. A leader making a financial or competitive decision under acute stress, something that taps into primal reward/threat circuits in the limbic system, might default to either aggressive risk-taking or total risk aversion depending on whether they appraise the situation as a challenge (opportunity for gain) or a threat (potential for loss). This appraisal process, mediated by the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex, can determine whether cortisol enhances approach or avoidance behaviors. By contrast, when deciding on an abstract policy matter in a meeting (perhaps less viscerally engaging), the stress response might not translate as strongly into decision bias, especially if there is sufficient time for deliberate, prefrontal-mediated analysis to override initial stress-driven impulses.

Gender appears to play a significant role in how cortisol influences risk-taking behavior. One study showed that cortisol can boost risky decision-making in men but not in women. In the experiment, male participants who received exogenous cortisol showed significantly greater risk-taking on a financial decision task, whereas female participants' behavior remained largely unchanged. Other research has similarly found that stress increases financial risk tolerance in males, whereas females under stress sometimes become more conservative or maintain their baseline approach. This variation is probably due to the interactions between cortisol and other hormones like testosterone, as well as differences in neural emotion processing pathways. This pattern aligns with evolutionary theories suggesting that males under stress might lean toward "fight or flight" risk-taking behaviors, whereas females might engage different coping strategies consistent with "tend-and-befriend" responses.

However, we must emphasize that these are statistical averages across large samples; individual leaders may not conform to their demographic trend. Substantial variation exists within each gender, and factors such as personality traits, experience, and organizational culture can override these general tendencies. Nevertheless, it remains valuable for leaders to engage in self-reflection: "How does stress typically affect my appetite for risk? Do I make aggressive, high-stakes decisions when pressure mounts, or do I become overly cautious?" Developing this self-knowledge can help leaders recognize their stress-induced decision patterns and implement safeguards to prevent potentially detrimental knee-jerk choices during high-pressure situations.

The Surprising Link Between Stress and Prosocial Behavior

Decision-making for leaders isn't just about numbers and logic; it is often about social decisions, the decisions made in social context about people, trust, fairness, and ethics. Cortisol influences social decision-making sometimes in surprising ways. Acute stress increases prosocial behaviors like trust and sharing. This seems counter-intuitive. Why would stress make someone more generous or trusting? One theory is that in certain contexts, our biological response may motivate us to seek social support and strengthen alliances as a coping strategy through the tend-and-befriend mechanism. In tasks where research participants decide whether to help or share with others, acute stress led to more altruistic decisions, and these decisions were positively associated with cortisol levels. In plain language, some stressed people (especially during or right after the stressor) were more likely to say "yes" to helping others or to divide resources generously, and those with bigger cortisol spikes were often the most generous.

Although stress-induced prosocial behaviors are often adaptive for building social bonds, they can also create vulnerabilities that manipulative individuals may exploit. People under acute stress may have an impaired ability to detect deception or ulterior motives, as their cognitive resources are focused on managing the immediate stressor. Workplace bullies and manipulative supervisors sometimes intuitively recognize these moments of heightened stress vulnerability. They may time their unreasonable requests, demands for favors, or pressure tactics to coincide with periods when you are already under stress. A department head dealing with budget cuts might find themselves more susceptible to a manipulative colleague's request for special treatment or resources during the height of the crisis. The elevated cortisol that makes the stressed administrator more inclined toward prosocial responses ("yes, I'll help") simultaneously impairs their ability to critically evaluate whether the request is legitimate or exploitative. When you're under significant stress, it may be wise to delay non-urgent social decisions or seek input from a trusted, less-stressed colleague before agreeing to requests that could be taken advantage of your temporarily heightened cooperative tendencies.

The stress-induced prosocial behaviors, however, are not universal. Stress can at times reduce trust or make people less forgiving, especially if the social situation itself is the source of stress (for example, feeling socially evaluated or threatened). Chronic high cortisol can also relate to irritability and aggression, as prolonged cortisol elevation leads to decreased emotional regulation and increased hostile attribution bias, where we interpret neutral behaviors as threatening. Although acute cortisol sometimes nudges toward conciliation (short-term stress prompting "let's stick together" behaviors), chronic stress appears to erode patience and generosity over time, potentially making initially prosocial leaders into more authoritarian or withdrawn decision-makers.

Leaders who develop awareness of these neurobiological processes can better recognize when stress might be compromising their judgment and implement strategies to mitigate these effects. Whether through stress reduction techniques, decision-making protocols, or simply pausing to reflect during high-pressure moments, such awareness can significantly improve leadership effectiveness.

The implications of cortisol's influence extend beyond individual decision-making to encompass broader organizational dynamics. In our next article, "Cortisol in the Organizational Context: Leadership, Power, and Hierarchy," we will explore how stress hormones shape not only individual choices but also power relationships, team dynamics, and organizational culture itself.